The Lebanon, Virginia, Farmers Market was bustling with activity on a rare calm and breezy Saturday after weeks of stifling heat. Amidst the lively crowd, I was drawn to a particular stall where a young couple sold homemade goods: freshly baked bread, cookies, golden honey, and the promise of grass-fed beef and lamb to come. The man wore a cap embroidered with “Lyttle Farm of Copper Ridge.”

I learned that this isn’t just any farm. It’s a Virginia Century Farm, a designation for farms that have been in continuous operation by the same family for over 100 years. Lyttle Farm has been a family legacy since 1898, nestled high on scenic Copper Ridge in Castlewood. The couple, Travis and Shiloh Brooks, told me the farm’s story is a testament to resilience and adaptation.

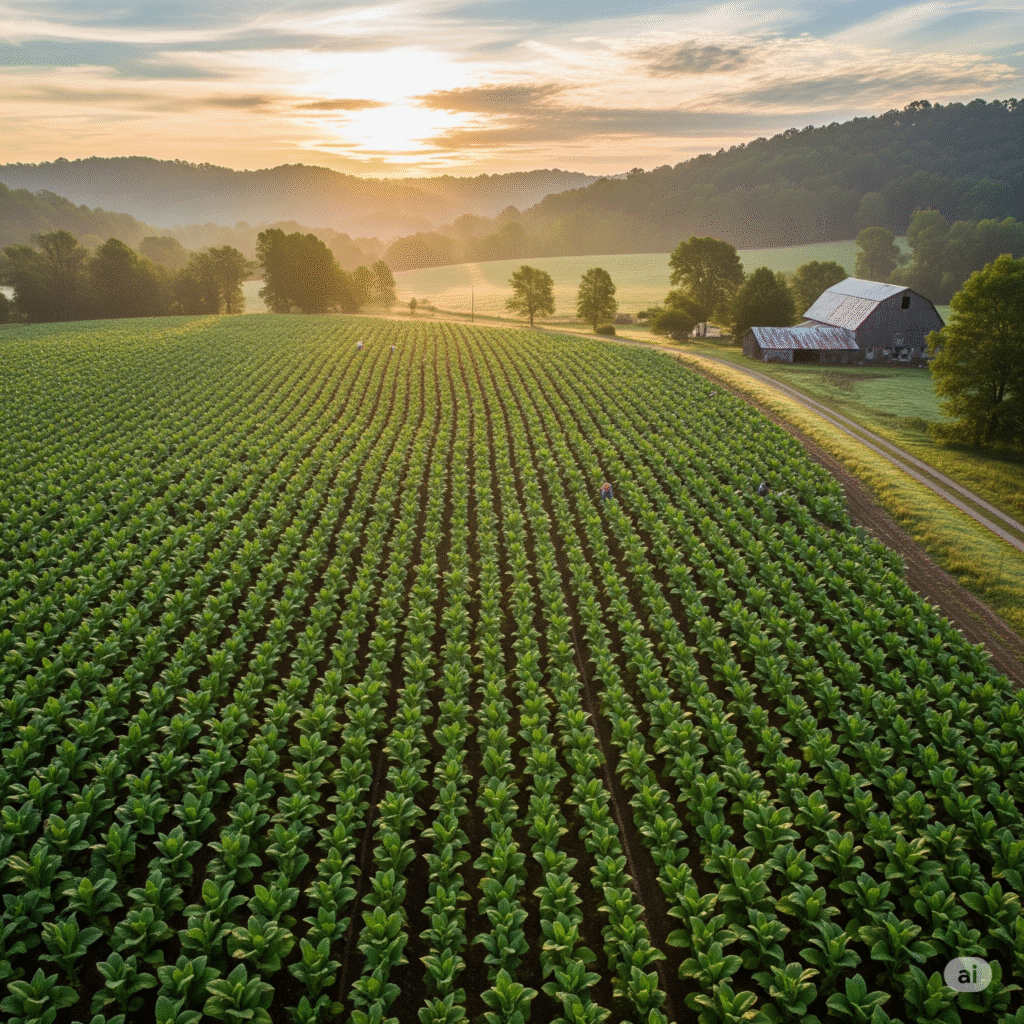

Travis, who married into the family, has been farming for five years. “It’s a big family thing,” he said, gesturing to Shiloh. “We try to keep it within the family.” Shiloh, who has been farming her whole life, explained that for generations, her family—starting with her great-grandfather—has primarily grown tobacco.

The Tobacco Buyout and a New Beginning

The turning point was the government’s tobacco buyout program. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the federal government, facing large lawsuits against major tobacco companies and a decline in the industry, established a program to pay farmers to stop growing tobacco. This buyout essentially eliminated the long-standing price support system that had sustained tobacco farming for decades.

This pivotal moment wasn’t the end of Lyttle Farm; it marked a new beginning. They shifted from tobacco to a more diverse operation that better reflected the changing tastes and demands of their community. “We’re really getting back into it,” Shiloh said, noting that they had taken a brief break due to family and health issues. She emphasized their commitment to providing high-quality, local food.

“Shop local, you know, support local,” Shiloh urged. “It matters what you feed into your body, and supporting your neighbor is always the best way to do it.” As we wrapped up our conversation, she pointed toward the market entrance with a smile. “You really should talk to my dad. He’s on his way right now. Oh, my dad will have a lot to say.”

From Tobacco to Sheep, Beef, and Alpacas

A little while later, Jim Lyttle, Shiloh’s father, arrived, and I had the chance to speak with him. With over 40 years of farming experience, he offered a rich, historical perspective. He recounted how he was growing tobacco when the buyout happened. “They took away our price supports,” Jim explained, “so we just took our buyout and invested.”

This investment resulted in a new type of farm. “We’re now into sheep, beef, and bees,” Jim said, “and we’ve got three alpacas out there.”

The mention of alpacas caught my attention. Jim explained that these fluffy, gentle creatures aren’t just valued for their fiber; they also make excellent guard animals. “They bond with the sheep or calves and just drive the predators away,” he noted, a fascinating detail I never would have guessed.

Finding a Niche in the Modern Market

A contract between a local supermarket chain, Food City, and the Scott County Hair Sheep Association facilitated the shift from tobacco to sheep. Food City was looking for locally sourced lamb. “That gave us a ready-made market to go into the sheep and lamb business,” Jim said. Although that contract eventually ended when the company found they could get lamb cheaper from New Zealand and Australia, Lyttle Farm continued to find its niche.

It turns out there’s a growing market for lamb, especially within ethnic communities. Jim discussed the opportunities in places like New Holland, Pennsylvania, where there are sizable Muslim and Jewish populations. “They’re specific. It has to be without blemish,” he said, explaining the strict requirements for Halal and Kosher butchering.

Halal is an Arabic term meaning “permissible” and is used within Islamic dietary laws. Halal meat practices involve slaughtering the animal quickly and humanely with a sharp knife while reciting a prayer. Kosher, which means “fit” or “proper” in Hebrew, refers to Jewish dietary laws. Kosher meat also requires a humane slaughter performed by a trained individual, along with the complete draining of the animal’s blood. Although there are subtle differences, both practices emphasize humane treatment and cleanliness, creating a niche market for conscientious farmers.

The Future of Farming

As our conversation shifted to the future of farming, Jim’s voice took on a somber tone. He worried about who would carry on the tradition. “The average age of a farmer in Virginia is 74,” he stated, a stark statistic that highlights an aging agricultural workforce. He mentioned that many farmers, tempted by offers from developers, are selling their land for housing. “Where’s our next generation of farmers?” he mused.

His daughter and son-in-law, Travis and Shiloh, are a source of great comfort and pride. “I’m very blessed to have a daughter and son-in-law who are interested in taking over,” he said. Their belief in their work is apparent, echoing Shiloh’s earlier sentiment about supporting local.

It was a sentiment I heard echoed among many of the younger farmers I’ve met. While the national average age of farmers stays high, a growing movement of young people is entering the profession, driven by a love for the land and a desire to provide healthy, local food to their communities. They are revitalizing old traditions, and on this cool and breezy Saturday in Lebanon, Virginia, it was clear that the legacy of Lyttle Farm is in good hands, passed down from one generation to the next with great respect for the land and the people it nourishes.